A few years ago, I attended a talk by Mark Sorrell. He was discussing gamification and some of the issues with it. He worked in the games industry, in fact, the now heads up the new London based office of Rovio (they of Angry Birds fame). It was a fascinating talk and one that introduced me to a concept that has fascinated me ever since, Cognitive Dissonance. A term coined in 1957 by Leon Festinger in his book A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance 1.

Cognitive Dissonance is the feeling of mental discomfort or stress a person may experience when they hold two or more contradictory beliefs. An example that Festinger offers is that of a smoker, who whilst knowing smoking is bad for their health, continues to smoke.

The reason this causes us stress, in Festigner’s view, is because as humans we strive for psychological consistency. To overcome this dissonance, we adopt certain mental strategies to bring about consistency. Let us consider an example. You see a person drop a $5 note on the floor, pick it up and keep it – even though you know that is wrong and you should have given it back to the person who dropped it. To relieve the discomfort of the dissonance that taking the money may cause, we can choose one of three basic strategies.

- Change our beliefs

- In theory, this is the simplest way to reduce the dissonance, just change what you believe about theft, convincing ourselves that theft is ok. However, this is much harder than it seems – as beliefs are set deep in our being and are not easy to change!

- Change of Actions

- Next, you could promise to never do it again. You can tell yourself that next time you will give the money straight back. However, this is predicting an event without understanding the circumstances that may lead to it the next time.

- Change in perception

- The final method is to change how you perceive the action of picking up the money. You change the story and how you remember it, creating justifications. It wasn’t really theft, you just found the money. Even if you had tried to give it back, you would never have caught up with the guy who dropped it. In reality, h had already disappeared into the crowd. This way you don’t have to make yourself promises of what you will do differently next time and you can still feel happy knowing you still believe theft is wrong – because what you did was not theft. Finders Keepers, Losers Weepers is a very powerful change in perception 😉

If you have ever read George Orwell’s dystopian classic 1984, you may recognise this as doublespeak and doublethink!

In our example of acquiring the $5 note from the person who dropped it, the above diagram can be adapted to show the following.

Privacy, Experiments and Facebook

An example of cognitive dissonance that we may have all come across is that of privacy in an online world. If you are signed up to Facebook, you likely know that you are signing away a large portion of your privacy. However, you alleviate any dissonance by changing how you perceive the value of Facebook compared to that loss of privacy.

“Facebook is really handy, I get to keep in touch with friends and family etc. Really, how important is it that they know my eveyr action and have more information about me than God, compared to just how great being part of Facebook actually is?”

There have been some fascinating experiments around how far we will go to justify our actions. In 1957, Festinger set up an experiment where people had to perform a very dull task. They were then paid either $1 or $20 to tell the next set of participants that the task was really exciting. Afterwards, those paid to tell others the task was fun, were asked to say if they enjoyed the task or not. Those paid $1 said they had enjoyed the task. The reason for this was explained by their need to reduce the dissonance created by knowing they were not being paid enough to lie. Instead of lying, they convinced themselves that they were not silly enough to lie for just $1, so they must have found the task fun!

This can be seen when people spend small fortunes or insane amounts of time playing games or on other hobbies. They know full well that it is crazy, but in their mind, they know they are intelligent and certainly not crazy, so the level of investment must have been worth it! They justify it by changing their perception of the action.

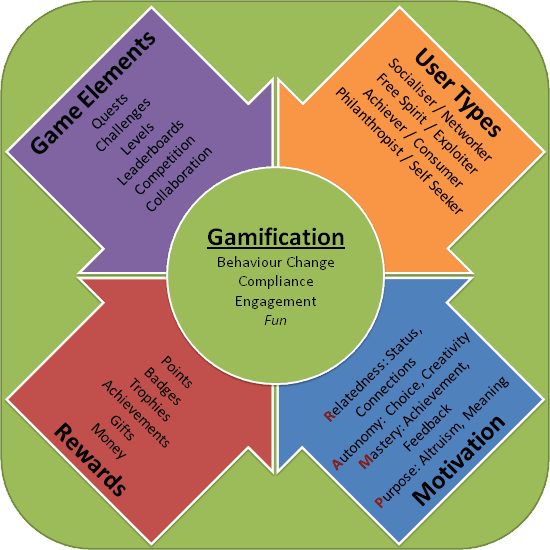

Gamification

When we consider gamification, this is something we have to be aware of in our solutions. Gamification can be perceived as manipulation, especially when it is being used to potentially modify behaviours that may, on the surface of it, not directly benefit the user. For instance, attempts to use gamification to increase productivity. On the one hand, the tools and methods being introduced may make the tasks easier or more enjoyable, but at the same time, it could potentially make a user feel that they are being forced to do it. This will not be the intention of the designer, but we have to take it into account. We need to look at it from an economist-like perspective and make sure that the experience and the solution bring high perceived benefits to the users, to alleviate this kind of cognitive dissonance. If they feel that the benefits outweigh any potential negative aspects of the system, then they will feel much more at ease using it. They also need to feel they have some level of control of what they are doing, again helping to reduce any perceptions of being manipulated.

Citations

- Festinger, L. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1037/10318-001

Similar Posts:

- 4 Simple Questions To Transform Your Gamification Implementation

- Gamification 2 Years On: what is it now, why is it still important?

- Gamification Check-lists for Implementation

Also published on Medium.